Setting an appropriate domain and context

Zonation is normally used within one of the following (partly overlapping) domains: curiosity-driven (research) science, issue-driven (regulatory) science (sensu van den Hove, 2007), and operational planning for conservation management. The distinction between these domains is not always clear, as large operational analyses will often require the development of novel methods, and many researchers actively seek to maximise the operational relevance of their research. Having a clear understanding of the domain within which your project falls is helpful, given the consequent differences in emphasis (Table 1). For example, a Zonation project commissioned by an environmental authority might place more on “getting it right”, because unsubstantiated results might compromise not only the utility of the results but also the credibility of the authority in the eyes of different stakeholders. From a technical point of view, this might be reflected in an increased emphasis on ensuring the quality of input data. We do not mean to imply that “getting it right” would not be important for curiosity-driven science and published papers, but simply wish to draw attention to the way that these emphases can differ depending on the analysis context. Demonstrating a scientific principle does not require the illustrative example to be policy-relevant and based on high-quality data.

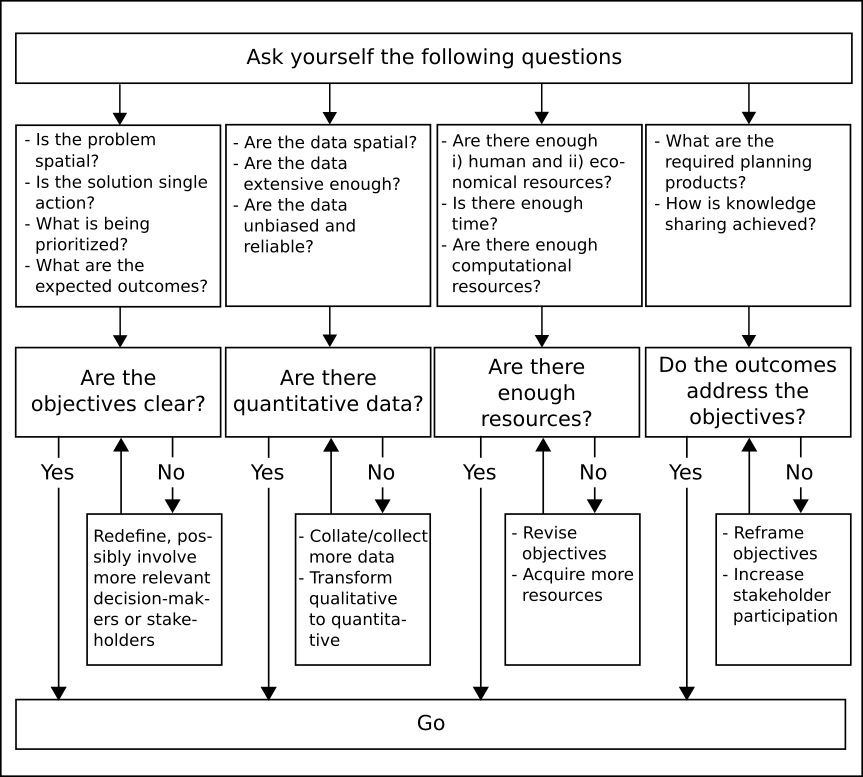

Figure 1. Relevant questions to ask when considering if Zonation (or any other spatial prioritization tool for that matter) is likely to be a useful tool for the job. The questions are best asked in parallel; objectives, available data and the resources needed are often closely intertwined. Note that requirements in scientific studies usually are lower than in policy-relevant on-the-ground applications.

Table 1. The three domains in which Zonation may be useful. Note that each real use-case will probably combine aspects from multiple columns. Table borrows from Jasanoff (1990).

| Curiosity-driven science | Issue-driven science | Operational planning | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Scientific insight, novelty, and significance | Knowledge relevant for forming and assessing policies | Application of existing knowledge |

| Products | Published scientific papers | Reports and white papers, often unpublished | Operational plans including maps, priority lists etc. |

| Important knowledge production components | Credibility | Relevance, legitimacy | Relevance, legitimacy |

| Decision-making context | Does not necessarily have one | An existing context, can also aim at establishing a new process | Embedded in an existing decision-making context |

| Accountability | To scientific community and professional peers | To political decision-makers, general public | To political decision-makers, civil servants, stakeholders |

Furthermore, there is an associated difference between executing a spatial prioritization analysis project using Zonation and developing a broader spatial conservation process in which Zonation will be the tool used to identify priorities. Consider the following descriptions:

An analysis project:

- Has an objective or outcome to be accomplished, and the project ends when that objective is accomplished. These are often scientific projects, but can also be practical projects such as, “Expand the regional conservation area network by 100 hectares of forested areas".

- The objective might evolve during the project.

- Has a beginning and an end, although the beginning and end may not be well defined when the project starts and the end might be a long time in the future.

- The sequence of tasks is not normally repetitive (except for what is required to identify and correct problems in analysis) and may not be fully known at the outset of the project.

- Is frequently based on an existing set of data, which is used to best advantage.

- Usually involves relatively few stakeholders.

A broader process on the other hand:

- Has an objective that is defined around the ongoing operations of an organization. For example, “develop the conservation area network of Finland”.

- Is a repetitive iterative sequence of tasks, which are typically known from the outset.

- Does not normally have an end defined at the time when Zonation is first used.

- Frequently involves multiple stakeholders and includes acquisition or improvement of data.

Although this difference might appear subtle, our collective experience indicates the importance of getting this right. In particular, the management of a prioritisation process as if it is simply an analysis project raises a serious risk that the overall goals will not be met. That is, the institutional and social framework required to successfully implement a prioritisation process require just as careful planning as the analysis component itself. For clarity and simplicity, we will here generally talk about running a Zonation analysis project except where the point is to specifically address issues related to using Zonation within a broader decision-making process.